BIAN ELKHATIB, LUIZA VAFINA,

and PIA LORENZEN

and PIA LORENZEN

A key to

the world

the world

For refugees, one German

class, many experiences

class, many experiences

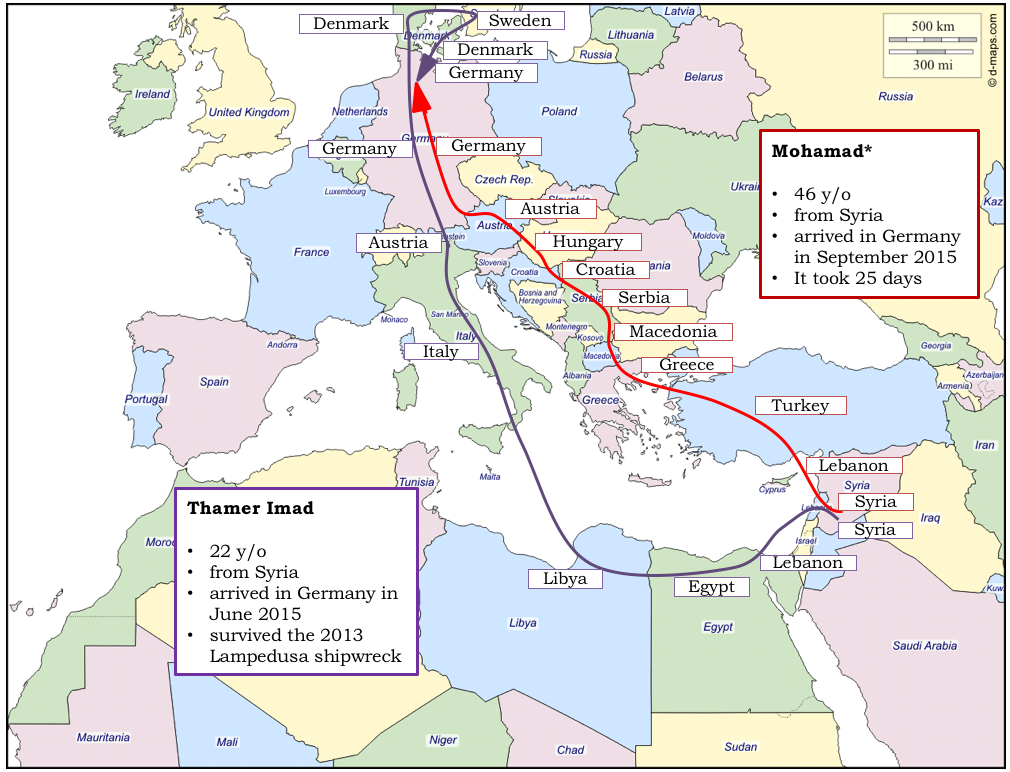

Thamer Imad is 22. Mohamed* is 46. Both are Syrian refugees living in Hamburg. But there is a crucial difference: One speaks German, one does not.

*Mohamed is an assumed name to protect his family in Syria.

*Mohamed is an assumed name to protect his family in Syria.

Mohamed sits on a bench on the banks of the Alster, a lake in Hamburg, as his black hair, streaked with grey, moves with the wind. He has been in Hamburg since September 2015 and is registered for German language courses, which will start sometime later this month. He does not speak German.

Mohamed, left, sits on a bench with his friend near Alster Lake in Hamburg, Germany, on June 10. (Luiza Vafina)

Imad, on the other hand, speaks German fluently. He has been in Germany since June 2015, following a treacherous journey on the Mediterranean Sea, where he survived the 2013 Lampedusa shipwreck, and a six month stay in an Italian hospital. Imad is currently participating in German language courses and hopes to gain permanent residency status.

In Germany, refugees from four countries – Syria, Iraq, Eritrea, and Iran – and immigrants with a residence permit are given access to integration courses that focus on the German language. Although the classes are the same, the students are not, and neither are their life experiences. That, paired with their family situation, can lead to struggles – and successes – when it comes to living in Germany and learning the language.

Tülay Beyoglu on why people learn German

"The most difficult German word for me is 'Entschuldigung', which means 'excuse me.'"

— Mohamed

— Mohamed

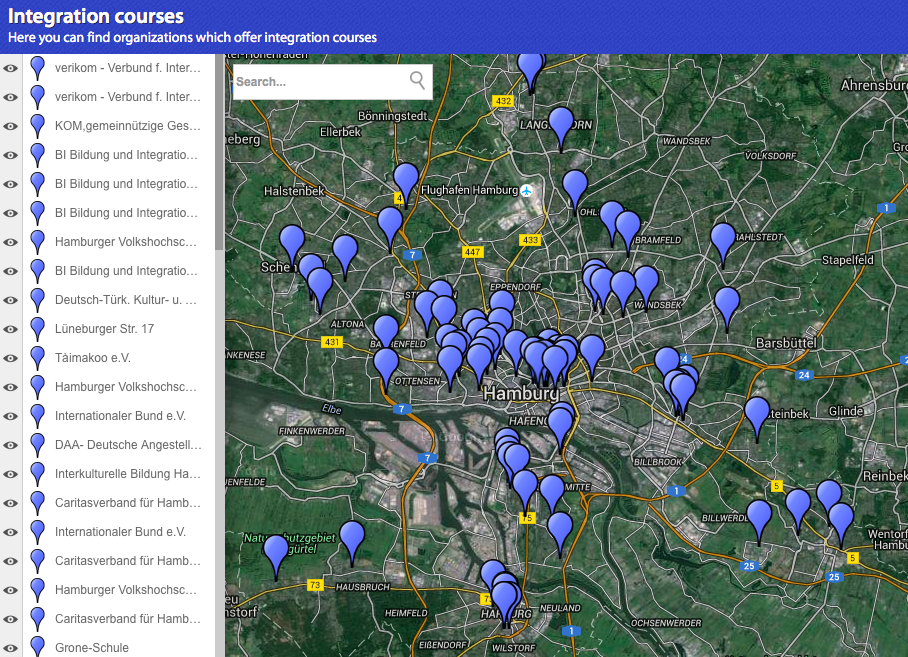

The number of attendees in Hamburg's integration courses are enough to make a small city – 6,437 people, according to the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees in Germany.

Of those students, Syrians comprise 19.2 percent of all German language class attendees, and Mohamed will soon be one of them.

Of those students, Syrians comprise 19.2 percent of all German language class attendees, and Mohamed will soon be one of them.

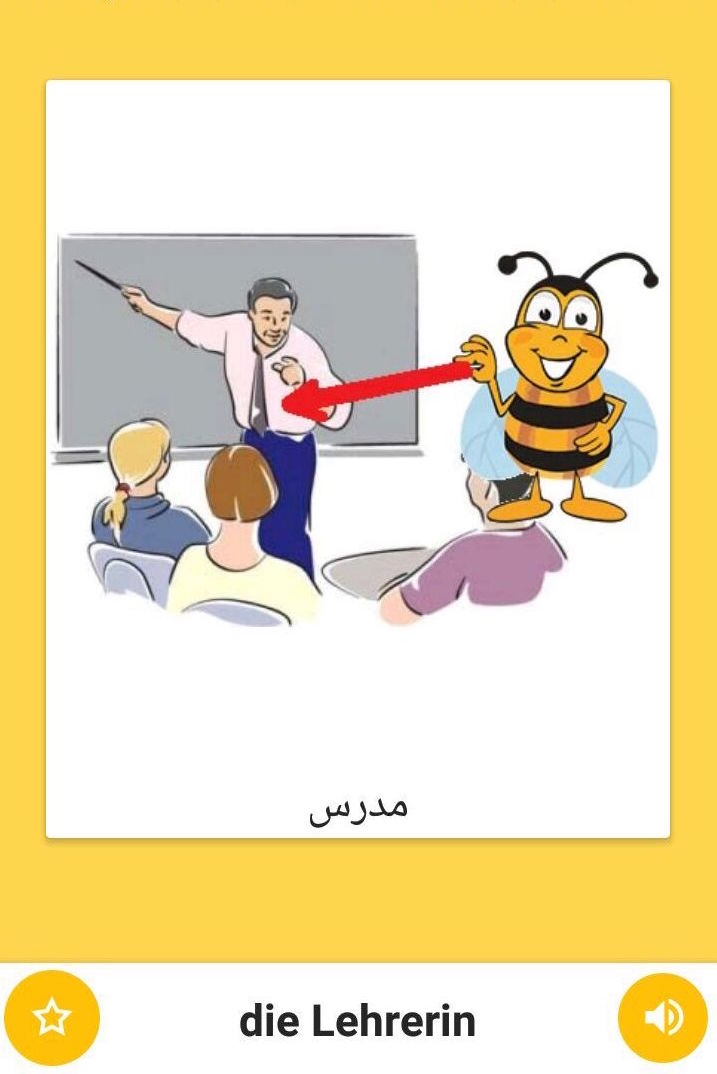

Until then, Mohamed keeps busy by reading a German grammar book and using a language app on his smartphone. Called "Fun Easy Learn German," he spends about one hour a day on the app.

"I mean, I learn from it. I sit, I use my headphones for an hour, two hours," Mohamed said in Arabic. "What I memorize, I memorize."

Without the classes, Mohamed said he doesn't think he can augment his language skills.

We have memorized, 'What is your name?' and 'Where are you from?' Simple stuff," he said.

"I mean, I learn from it. I sit, I use my headphones for an hour, two hours," Mohamed said in Arabic. "What I memorize, I memorize."

Without the classes, Mohamed said he doesn't think he can augment his language skills.

We have memorized, 'What is your name?' and 'Where are you from?' Simple stuff," he said.

A screenshot of the app Mohamed uses to learn German.

Where are integration courses offered in Hamburg?

On this map, you can find organizations that offer German language courses.

So what can Mohamed expect when he does eventually start his class? Students in integration courses take 300 hours of language classes. Most start at the basic level A1, a class that focuses on the essentials of the German language. After each class, students need to take a test, affirming they've mastered a certain level of the language.

The courses go up to the advanced level C2, but most refugees only make it to B1. Taking further tests means paying about 1,000 euros.

The courses go up to the advanced level C2, but most refugees only make it to B1. Taking further tests means paying about 1,000 euros.

Language levels in integration courses

A

Basic language use (A1 and A2)

B

Self-consistent language use

(B1 and B2)

(B1 and B2)

C

Capable language use (C1 and C2)

Imad is preparing to take test A2, and he's learning through both his integration courses and his time spent speaking German in Cafe Refugio.

He's also learning at home, where he lives with his brother. Both made it a point to converse in German, not Arabic, so they can exchange the vocabulary words that both are learning.

"I think it's better when a man wants to learn something like that," Imad said, adding that it is better to speak only one language to facilitate learning.

He's also learning at home, where he lives with his brother. Both made it a point to converse in German, not Arabic, so they can exchange the vocabulary words that both are learning.

"I think it's better when a man wants to learn something like that," Imad said, adding that it is better to speak only one language to facilitate learning.

Imad on learning German

Mohamed, on the other hand, wishes he could practice his German with others, saying he feels isolated in Germany. Part of the reason for that feeling is that he's living in a refugee camp in the Wilhelmsburg district.

"Our peers are Arab, an Arab complex," Mohamed said. "We don't feel like we have joined Germany. Once we leave this camp, we feel like we are in Germany."

"Our peers are Arab, an Arab complex," Mohamed said. "We don't feel like we have joined Germany. Once we leave this camp, we feel like we are in Germany."

What's it like to live in the camp? An inside look

Because Mohamed doesn't speak the native language, he's often worried about leaving the camp unaccompanied when he goes to restaurants, shops and stores.

"I don't go out alone, because he (the vendor) doesn't understand me, and I don't understand him, and then there will be confusion," he said. "They say you have to learn German and a person needs to learn German by speaking [the language]."

"I don't go out alone, because he (the vendor) doesn't understand me, and I don't understand him, and then there will be confusion," he said. "They say you have to learn German and a person needs to learn German by speaking [the language]."

He said that in the nine months he's been here, no one has approached him and spoken German. However, on Fridays, he meets with a German acquaintance and plays chess, a language where no speaking is necessary.

"In the end, there isn't anyone to speak to," Mohamed continued. "Are you going to speak to a mirror?"

"In the end, there isn't anyone to speak to," Mohamed continued. "Are you going to speak to a mirror?"

Julia Koldehoff on the diversity of German classes

Mohamed has two children, 16 and 12, who are still in Syria. Although he has been in contact with the Red Cross to get them into Germany, he is worried about them.

"I think of my kids a lot," Mohamed said, indicating that his concern for them can interrupt his learning a new language. He is convinced it does, and he's not the only one who thinks so.

"I think of my kids a lot," Mohamed said, indicating that his concern for them can interrupt his learning a new language. He is convinced it does, and he's not the only one who thinks so.

Tülay Beyoglu, a social worker at Verikom, an integration center for migrants in Hamburg

"Some refugees … still think about [their] children, who might have been left [behind]. Sometimes it is more important to find a way how to bring the left family members to Germany. Afterwards they can be asked if they want to do a German course. The first thing is to find out what is the most important thing for the person and what is he prepared for."

Still, there also are other factors impacting Mohamed.

Back in Syria, he worked at a supermarket, where he ran the cash register and stocked groceries for 20 years. He left school after ninth grade. Mohamed can only take 900 hours of German classes for free. Afterwards, he will be responsible for the costs.

"They want us to learn German in a year (to) a year and half." He doesn't think he will have learned the language in the available time.

Back in Syria, he worked at a supermarket, where he ran the cash register and stocked groceries for 20 years. He left school after ninth grade. Mohamed can only take 900 hours of German classes for free. Afterwards, he will be responsible for the costs.

"They want us to learn German in a year (to) a year and half." He doesn't think he will have learned the language in the available time.

Silke Schuff, Bildung und Integration Hamburg Süd gGmbH, an integration center for refugees in Hamburg

"When we speak about studying, the age doesn't matter. I believe an educational background seems to be much more important. For example, [a] 60-year-old man who speaks foreign languages and is familiar with [the] Latin alphabet, would learn [the] German language easier than young boy, even if it is believed that youngsters catch on faster."

Refugees taking German language courses in Cafe Refugio

"In the end, there isn't anyone to speak to. Are you going to speak to a mirror?"

— Mohamed

— Mohamed

While Mohamed struggles with both age and education, it is an asset for Imad. He left school after his second year in college, where he was studying mechanical engineering.

The first language Imad learned was English. He learned it in six months after the boat he was fleeing to Italy on capsized, he was hospitalized.

"I would listen to what the people were saying. For example, I have a lot of friends that would speak English. My brother speaks English. I would listen to how they talk, and I slowly would start to learn English," Imad said in Arabic.

Both men are working to keep learning, and this is just the beginning.

Mohamed plans to go further than just the German language. After completing his classes, he hopes to go back to school to become an electrician.

Imad, too, said he wants to continue his education, and would like to become fluent in Spanish and French.

"When I was in Syria, I didn't want to learn any other language. But now, I want to learn languages."

The first language Imad learned was English. He learned it in six months after the boat he was fleeing to Italy on capsized, he was hospitalized.

"I would listen to what the people were saying. For example, I have a lot of friends that would speak English. My brother speaks English. I would listen to how they talk, and I slowly would start to learn English," Imad said in Arabic.

Both men are working to keep learning, and this is just the beginning.

Mohamed plans to go further than just the German language. After completing his classes, he hopes to go back to school to become an electrician.

Imad, too, said he wants to continue his education, and would like to become fluent in Spanish and French.

"When I was in Syria, I didn't want to learn any other language. But now, I want to learn languages."

Project of the International Media Center at Hamburg University of Applied Sciences in cooperation with School of Journalism & Mass Communications at Saint Petersburg State University and Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated marketing communications at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois